Mickey Cohen looks over the damage after a bomb shattered part of his Brentwood home and damaged neighbors’ houses, February 1950

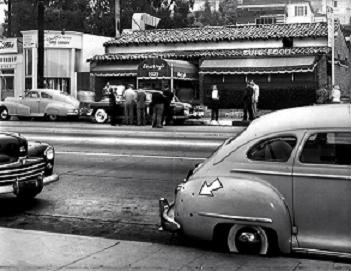

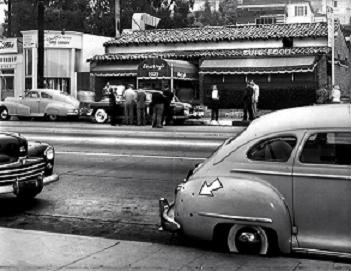

This photograph was taken from the vantage point of the gunmen who fired at Mickey Cohen and his companions outside Sherry’s, July 1949

This photograph was taken from the vantage point of the gunmen who fired at Mickey Cohen and his companions outside Sherry’s, July 1949The Sunset Wars had begun when a man in a Panama hat fired a shotgun into Mickey’s clothing store on the Sunset Strip, killing one of his cadre of henchmen dubbed the “Seven Dwarfs.” Some suspected that Mickey had set up his own man because he ducked into the bathroom before the shooting — not everyone understood that the gang boss suffered from an uncontrollable urge to wash his hands.

She got the cops boiling again by passing on to readers a theory “a lot of people have” — that the ambush wasn’t the work of Mickey’s rival, Jack Dragna, but that the LAPD was somehow behind it.

Yet another of Mickey’s Dwarfs disappeared Labor Day weekend after he was supposed to dine with Jimmy “the Weasel” Fratianno. One more vanished a month later.

By fall 1949, Mickey could claim a scalp of his own, that of Police Chief C.B. Horrall.

This episode began when vice officers arrested another of Mickey’s men for illegal possession of a weapon. Enraged, Mickey arrived at his underling’s trial with his personal bugging expert, 300-pound J. Arthur Vaus, and announced that they were going to blow the lid off the LAPD.

It seems that a vice detective working out of Hollywood had hired Vaus to eavesdrop on the Strip’s leading madam, hoping to document her unholy relationship with a rival vice cop from downtown. But the madam insisted that she was paying off both cops, and Mickey’s rotund bugger said he had the damning evidence on magnetic wire. They brought a recorder to court and plopped it on a table, daring anyone to call their bluff.

http://www.g4tv.com/thefeed/blog/post/712724/interview-la-noires-patrick-fischler-spills-the-beans-on-playing-mickey-cohen/

She got the cops boiling again by passing on to readers a theory “a lot of people have” — that the ambush wasn’t the work of Mickey’s rival, Jack Dragna, but that the LAPD was somehow behind it.

Yet another of Mickey’s Dwarfs disappeared Labor Day weekend after he was supposed to dine with Jimmy “the Weasel” Fratianno. One more vanished a month later.

By fall 1949, Mickey could claim a scalp of his own, that of Police Chief C.B. Horrall.

This episode began when vice officers arrested another of Mickey’s men for illegal possession of a weapon. Enraged, Mickey arrived at his underling’s trial with his personal bugging expert, 300-pound J. Arthur Vaus, and announced that they were going to blow the lid off the LAPD.

It seems that a vice detective working out of Hollywood had hired Vaus to eavesdrop on the Strip’s leading madam, hoping to document her unholy relationship with a rival vice cop from downtown. But the madam insisted that she was paying off both cops, and Mickey’s rotund bugger said he had the damning evidence on magnetic wire. They brought a recorder to court and plopped it on a table, daring anyone to call their bluff.

A grand jury did. It had the wire recordings seized and discovered they’d been erased. In one of the more bizarre chapters of a bizarre time, Vaus attended a Billy Graham crusade, found the Lord and confessed his sin — he’d lied about the tapes.

The problem was, the grand jurors by then were convinced that LAPD officials had to be covering up something and indicted the chief and several others for perjury. Though Horrall was exonerated, he’d had enough of such intrigue and retired to his farm in the San Fernando Valley.

That left Mickey to gloat that he’d taken down the city’s top cop — and left the Gangster Squad without its founder and protector.

When the LAPD got its permanent new chief on Aug. 2, 1950 — the one who would revolutionize police work in the U.S. — he wanted to know what those characters were doing in his office. William H. Parker was a lawyer and distinguished soldier, having helped plan the detention of captured Germans after the Normandy invasion. As a cop, he was the great exponent of Internal Affairs, of policing your own tougher than you policed the city. No more vice cops helping themselves to a local madam. And perhaps no more Gangster Squad.

By then, the squad had advanced from meeting on street corners to a small office in the decrepit Central station to digs at the seat of power, in City Hall, right next to the chief’s suite. Sgt. Jack O’Mara was smoking his pipe, perusing the Teletype, when the new chief stopped by. A few others were typing reports about who had been seen having drinks with various hoods the night before. “Parker came into our office, ‘What the hell do we need “Intelligence” for?’ you know. And his adjutant told us, ‘He’s going to derail you guys.’ ”

Parker put his aide, Capt. James Hamilton, in charge of the squad and prepared transfer orders for O’Mara and the others, pegging several for traffic duty.

The prospect was crushing to O’Mara, who’d done the dirty work of the Gangster Squad. He’d taken out-of-town hoods up to Mulholland Drive for a talking-to and a gun in the ear. He’d helped plant bugs in Mickey’s shoe closet and TV. Now they were going to have him writing tickets for double parking.

O’Mara figured he might as well make one last run at Mickey. He had seen an opening when he discovered that one of the security guards at the Cohens’ Brentwood home had a warrant hanging over him. So he “encouraged” the guard to quit and recommend “a buddy” to Mickey as his replacement. The “buddy” was Neal Hawkins, who’d been a munitions expert in the war, a credential sure to appeal to Mickey. But he also was a certain cop’s paid informant.

Hawkins earned his money that summer by alerting O’Mara to comings and goings at the house. He thus reported when Mickey planned a trip to Texas with, of all people, Florabel’s husband, Denny Morrison, a former newspaper copy editor and film publicist. When O’Mara tailed them to the airport, he found that they had registered for their flight as Denny Morrison and Denny Morrison Jr.

O’Mara cabled the Texas Rangers that Mickey Cohen was headed their way under an alias. Then he left a note to the Gangster Squad’s morning shift and went home to bed.

The Texas Rangers treated Mickey’s arrival as akin to Bonnie and Clyde coming back from the grave. They rousted him big-time, then called the press to show off their catch.

O’Mara was awakened by a call from a supervisor: “Your ass is in a sling.” The publisher of the Mirror, Virgil Pinkley, was getting calls asking what the spouse of his star columnist was doing with the city’s most notorious hoodlum. But when he phoned Florabel, she denied her hubby was in Texas. As it was explained to O’Mara, Pinkley asked, “Well, where is your husband?” and Florabel replied, “He’s asleep — you want me to get him?” The publisher took her word for it, then phoned Chief Parker to complain about that damn squad that couldn’t get anything right.

Florabel Muir had the nerve to ask, “What does a Gangster Squad do?”

Florabel Muir had the nerve to ask, “What does a Gangster Squad do?”

She was the epitome of the hard-boiled newspaper dame: born in a Wyoming mining town, a veteran of New York’s tabloid battles and now, in 1949, author of a Los Angeles Mirror column that served up Hollywood news while mocking the LAPD as “cops a la Keystone.”

A crowd was waiting at the L.A. airport when Mickey returned, quipping about his ill-fated visit to the Lone Star State: “Well, the food was good.” Then who should get off the plane, trying to slip away, but Mr. Florabel Muir.

Florabel tried to shrug off the incident, saying her husband was only helping Mickey search for one of his missing henchmen — nevermind that Mickey gave a different explanation for the trip, some story about an oilman and a lucrative card game.

What counted to Parker, one month on the job, was the praise he got from the head of the Texas Rangers and the apology he got from the publisher of the paper that had been clobbering the LAPD.

Parker and Hamilton held off on disbanding the squad. Oh, they did give it a sanitized name, the Intelligence Division. But under their watch, it would grow to 60 investigators, and the mission of many — and the obsession of a few — would be taking down Mickey Cohen.

It became clear that Mickey himself was a target in July 1949, when he was shot in the shoulder outside Sherry’s cafe at 9039 N. Sunset Blvd. The blasts killed another in his crew and sent two women to the hospital: a bit actress described in The Times as “Miss Dee David, a blond,” and Florabel, who took a pellet in her hindquarter. Florabel said she’d been hanging around Mickey to get a story, “waiting for someone to try to kill him.”

This photograph was taken from the vantage point of the gunmen who fired at Mickey Cohen and his companions outside Sherry’s, July 1949

This photograph was taken from the vantage point of the gunmen who fired at Mickey Cohen and his companions outside Sherry’s, July 1949

You must be logged in to post a comment.